How to dismember a park and get away with it

There are lots of new social housing developments firing up at the moment, as part of the Victorian Government’s $5.3B “Big Housing Build”. The “Build” was announced soon after the public housing tower lockdowns focused eyes on the long-neglected sector.1 There is a lot going on, so I’ve narrowed it down to just one development not too far from me, and I’ll be looking at the site more than the buildings.

The development at Unity Park and its surrounds sits at the Wellington Street end of the Collingwood housing estate. Two new eight storey blocks containing 150 households are proposed for what is already one of the densest precincts in Melbourne. They are to be built next to the existing 20 storey tower.

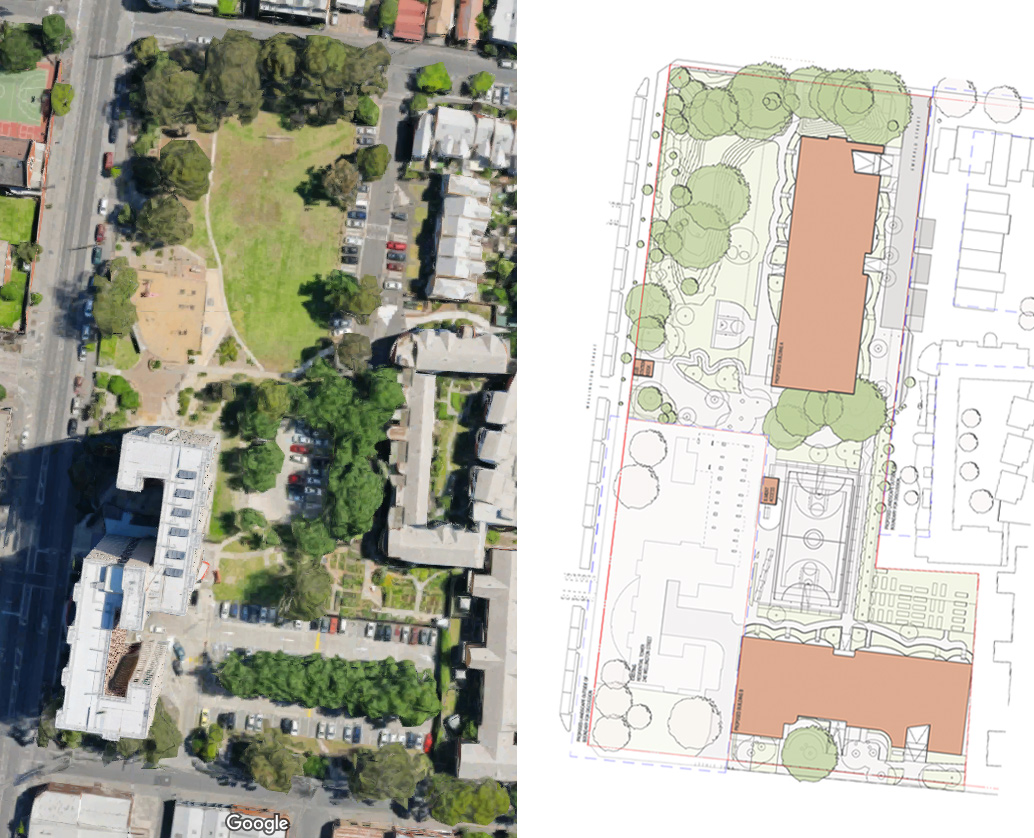

While the social housing block will take over an at-grade car park (which the residents aren’t exactly happy about), the northern affordable housing block takes up half of what was once the Emerald Street park. This “restricted” public park was renamed Unity Park in 2015 when much of the grassed open area was transformed into a basketball court.

Unity Park opening at Wellington st with

— Martin Foley (@MartinFoleyMP) November 21, 2015rwynnemp</a> <a href="https://twitter.com/robertocolanzi?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">robertocolanzi & 100s of #collingwood finest #springst pic.twitter.com/jaAQ759a1Z

Here’s what the site looked like before the basketball courts went in (left), and the new development (right).

Site plans – before and after

According to the development summary there will be more open space than there was before – up from 67% “useable open space” to 71% “open space”. I’m not sure how that adds up, but guess it’s because the large southern car park and another smaller one, both at-grade, are not deemed to be “useable” open space. Clever.

From what I can determine, the entire site except the existing tower quadrant at the south west, will pass into private ownership. Other sites will be leased for 40 years – this one is not on the list. Information about land tenure is not available.

Here are the buildings.

Sun-drenched southern elevation, Vere Street

View of the northern building from Wellington Street

The southern “social housing” block is not much to look at. Its no-frills palette makes it look cheaper than it probably needs to, and hints at a shift from the former DHS’s stipulation that the Atherton Gardens social housing, built ten years ago, look nothing like public housing. In that development, the social and affordable components were integrated. At Collingwood they are to be separated by the relocated basket ball court. The buildings have the same bones, but the northern “affordable or market housing” block is a touch more glamorous, with green-coloured trimmings on the balconies. (Trying to find out how “affordable or market” housing is defined, who is eligible for it, and who will own it and manage it, led me down a mirror-lined rabbit hole… so I’ll leave that to the side for now.)

Reading a few of the renderings against the plans and elevations shows that an artist’s license is in effect – nothing out of the usual. The lighting is optimistic, the points of view unlikely and open space is emphasised over built form. In the second image, the new building is made diminutive by the big tower, big sky and big foreground. You would think the building is bordering a large park rather than taking up almost half of it.

The preference for the wide angle view is common enough in architectural renderings – it fits a lot in from up close and adds spaciousness and dramatic angles where none exist. I think though that when renderings are being used to inform community consultation, as these were, the view should be a little closer to what human eyes would see than what my phone camera sees.

I’ve wrangled Google Earth, Street View, the existing render and plans and elevations to come up with a crude “before and after” using a field of view that’s a bit closer to humanoid (and lands you in the middle of Wellington Street). I’ve also removed some trees so that the park’s low-rise context is visible.

before

after

Why should the social housing building look like the poor cousin? I wouldn’t like to speculate, but this step down does fit with the government’s “housing continuum”. Social housing is inferior, only a couple of steps away from sleeping on a park bench. It’s a long way from private home ownership – which is for them the bee’s knees.

The housing continuum, Home Vic strategy guide, 2021

The internal planning and massing are similar to what you might see in a mid-rise “market rate” apartment block. Following the new norm, everything is around eight storeys high. I don’t know where that magic height came from, but it’s a “known known” that it isn’t a healthy height for this sort of housing. According to a thorough evidence review, anything over three storeys is going to be harmful to the mental and physical health of the occupants, and harmful to the neighbourhood.

“A [2007] study of four disadvantaged sites in Melbourne, Australia (two high-rise and two detached homes) found that high-rise dwellers had greater negative perceptions of the neighbourhood that led to poor health and well-being than did residents in detached homes, thus leading to the conclusion that a concentration of disadvantaged people in a high-rise building not only increases crime and insecurity for the surrounding area but decreases mental health for the residents.” High-Rise Apartments and Urban Mental Health—Historical and Contemporary Views

The authors of this review found no research into the effect green space has on the health and wellbeing of low income tower residents. The effect on tower residents across all income brackets has been studied – “if greening strategies were employed around the high-rise buildings so that residents could be exposed to green space, studies have shown that they would report fewer symptoms of psychological distress.” Is it to much to assume the removal of half of a neighbourhood’s green space might have the reverse effect? An earlier report by Deakin and Beyond Blue thought so.

“The serious health and well-being implications of reduced access to green, open spaces for people living in socio-economically disadvantaged areas is significant and warrants serious consideration in future urban renewal and development projects.” Beyond Blue to Green, Deakin 2010

Mental and active health initiatives do exist in the project’s Sustainability Management Plan, but it comes in the form of health support staff for the construction workers, not in the design for the future residents. The Green Star Building questionnaire makes no mention of access to green space nor occupant health. It does refer to the building’s open space surrounds, but only in the context of threatened ecosystems and the proper reuse of land. The development is aiming for full marks for the latter as “75% of the site was previously developed land”. “Developed” is a fairly loose term.

A reason for the omission of occupant health and healthy surrounds is that they’ve measured the project against Green Star – Design and As Built. This tool was superseded in late 2020 by Green Star Buildings, but was not fully phased out until the end of 2021. The new rating tool redefines sustainable building to include social sustainability and climate change targets. Maybe next time round.

It’s an especial pity that they chose to use the old building-focused tool, as the government intends to use 2,000 homes in the Big Housing Build to house people living with mental illness – that’s almost a quarter of the social housing being provided.2

Unity Park (eastern half)

In order to get this urgent work shovel-ready pronto, the government has “taken in” the projects – given itself the right to skip over local councils and VACT appeals. They tend to do this when they think something has “state significance”, which usually means there will be lots of jobs. This roughshod ride through planning red tape has become the government’s go-to way, despite the failures along the way – such as the prolonged and compromised CUB site development in South Carlton.

The local greens-backed council, the City of Yarra, holds little sway over the housing site. After a recent skirmish over a social housing proposal on nearby Hoddle Street, their relationship with the Housing Minister reached a new nadir.

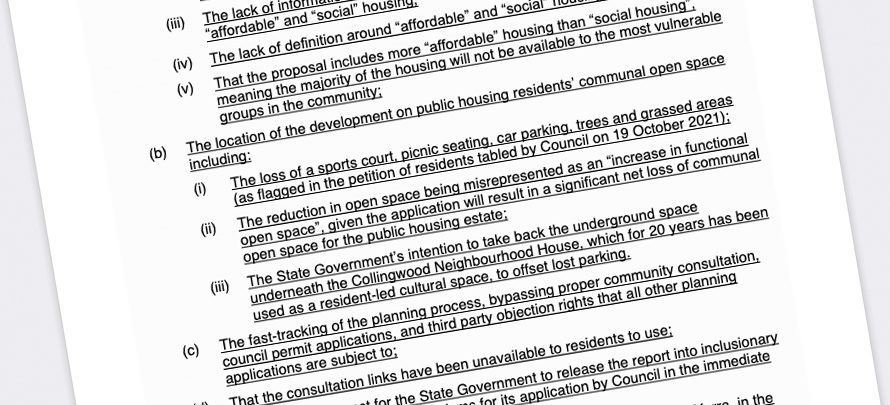

Though the project has been taken in by the state government, Yarra planners did recommend approval in November.3 That approval was subject to an avalanche of conditions, many just seeking absent detail. Buried within it all is a request for an environmental assessment of the site, which should recommend “whether the land is suitable for the use for which the land is proposed to be developed”. The development “must not be undertaken unless the Statement clearly states that the land is suitable for the sensitive use for which the land is being developed”. If the planners were tiptoeing around the issues, the carried resolution was not. Council was scathing of the proposal. Here’s a taste.

Despite the planning department being the self-nominated Responsible Authority, Yarra officers expect “a lot of that responsibility to fall to council.” This is due to the department’s lack of local and technical knowledge in some areas.4

Metro Melbourne residents have the poorest access to green space of any capital city in Australia5. Yarra rates Collingwood as its worst precinct in the open space stakes. 0.3% is “open” compared to 24.6% in neighbouring Clifton Hill. The state government has some defunct tools for measuring access to open space. This neighbourhood is rated as the most deprived in Collingwood.6 In its Open Space Strategy 20207, Yarra estimates a near doubling of residents and workers in Collingwood from 2016 to 2031. They’d better bring exercycles and pot plants.

I think the problem here is that the wrong arm of government has responsibility for this open green space. The oddly named Department of Families, Fairness and Housing seems to view its green space as a detachable asset that can be sold to fund its services. Selling off an existing housing estate’s green space for a temporary and miniscule improvement to the state’s chronic social housing deficit is like… selling an organ to fund a hair transplant.

You can see more of the plans here, for a limited time.

1 Melbourne’s tower lockdowns reveal the precarious future of Victorian public housing

2 Dept of Health: Supported housing for adults and young people living with mental illness

3 City of Yarra minutes 09.11.21

4 Yarra council meeting webcast 25.01.22 See from 20mins.

5 State of the environment 2016

6 Vic Gov: Metropolitan Open Space Network

7 Yarra Open Space Strategy 2020

Credits: Some images from Homes Victoria’s Engagement page, architectural design by Fieldwork; landscape design by Openwork; ESD engineering by ADP.

Posted by Peter on 27.03.22 in housing

tags: carparks, homelessness, housing, public housing, public space

comment

Thank you for a very well considered and researched article which describes very accurately this disgraceful proposal. Under the cloak of social concern, this State Government is selling off precious, scarce, and vital local park assets for very little social gain and strongly to the detriment of the highly disadvantaged people living in social housing in the area. That they have put themselves in an unassailable position by stymying the usual Council and VCAT processes bespeaks the worst arrogance, even corruption, on their behalf.

by Peter Enright on 18 April 2022 ·#

Petition is here https://chng.it/fwTbdtryKV

by Comatoes on 3 May 2022 ·#

Commenting is closed for this article.