Swanston street wall - Prevention matters

Six years have passed since a brick wall collapsed on Swanston Street in central Melbourne, ending the lives of three students walking by. In the early days authorities rushed to be seen to be doing something, placating a city wanting answers. Placating the hundreds of thousands who’d walked passed that same wall assuming that it was someone’s duty of care to ensure that big walls don’t fall onto busy footpaths.

The Coroner handed down her findings last June. No inquest had been held, though it would seem to fit the bill for one:

“An inquest is held because the coroner believes there is some issue of public importance, or he or she needs more information to answer all the questions about the death.” The Coroners Process, 2013, p39

Media reports on the findings were brief, focusing on one phrase: “the onus to ensure structural stability of the wall for attachments of hoarding rested with the owner of the site, which in this case was Grocon”. Newspapers didn’t mention that this clause was part of a note within a section dealing solely with WorkSafe’s visit to the wall in October 2011. It is not the Coroner’s role to apportion blame.

The findings incorporated responses by a few of the parties, stating how they’d taken steps to prevent a re-occurence. The Victorian Building Authority (VBA) and Worksafe said that they’d issued letters, toolkits and alerts to building practitioners and councils. Neither suggested any amendments to legislation or to their own operations.

Aussie Signs responded that it has not taken any action as it has moved its business away from sign installations. The company shrank from view the same year, but stablemates Billboard Media and Hugo Printing, sharing Aussie’s fax number and premises, continue.

Grocon said it had extended “contractor oversight” procedures to better monitor sub-contractors’ activities. Grocon also says it now engages independent engineers to assess all temporary structures on their development sites.

These moves were either short term or localised. At a state level, the State Coroner concluded that amendments to the Building Act Section 16 in 2016 adequately addressed “prevention matters”.

Google Street View, March 2013

Section 16

The amendments were introduced to parliament late in 2015, tacked onto the end of a larger suite of changes seeking, “to improve protection from home building malpractice”. Together, these changes were collected into the Building Legislation Amendment (Consumer Protection) Bill 2015, described by Maddocks lawyers here.

According to the findings, the earlier wording (“A person must not carry out building work unless a building permit in respect of the work has been issued”) prevented the Victorian Building Authority from charging any of the Grocon subsidiaries or Aussie Signs. They were only able to charge the person on the tools, even though that person did not have the authority to obtain a building permit.

The 2016 amendment required land owners, building practitioners and architects to ensure that a building permit had been issued where one was required. This would appear to have plugged a gap… except for the escape clause. Having legislated that owners must have a permit before commencing work, they are then allowed off the hook if they have employed a building practitioner or architect on the project, which is almost all of the time. This could extend liability across the project team, while indemnifying the land owner.

In two articles in 2016, Maddocks pointed out that the owner is still the applicant for a building permit. If a frustrated owner proceeds with demolition or construction without a permit, liability could sway towards consultants and contractors who may well have objected. This liability could still hold if the consultant had left the job before construction. “The architect, draftspersons, engineers or quantity surveyor engaged in the building projects could be in breach of s16(4) by virtue of the fact that they were engaged to prepare or advise on the design and they did not ensure that a building permit was later issued.”

I’ll repeat that last part in case you skimmed over it. An architect who has resigned from a job could be in breach of s 16 if, “they did not ensure that a building permit was later issued.”

Section 16 was put to the test in 2018, in a case (Brooker v Chelvadurai) involving a building site in the City of Maroondah. In short, a civil engineer who issued a limited certificate of compliance found himself in court because the broader project did not have a building permit. After much debate over the meaning of “building work”, which included a detailed examination of the minister’s parliamentary reading, the magistrate dismissed the case. As the case was heard in a Magistrate’s court, his ruling cannot set a binding precedent for other cases.

Though the Coroner found that the Section 16 amendments addressed “prevention matters”, they seem remote from the particular problems at Swanston Street – the boundary wall’s blurred jurisdiction, the uncertain status of the vacant site, the steady deterioration of the site since the CUB factory was demolished, and the circumstances of the collapse itself. Rather than try to prevent a similar incident, s 16 seeks to more efficiently flog anyone within coo-ee after such an event.

To follow a law you need to know about it. All of the senior architects I spoke to were blissfully unaware of the changes to s 16. An insurance broker just sighed when I asked about it. Oh, and then s 16 changed again.

All Victorians need confidence in the regulation of building in our state, and any registered practitioner who conducts work without or contrary to a building permit gives everyone in Victoria cause for concern. By including new indictable offences in relation to building works in contravention of the act, regulations or a building permit or building works without a permit this act can restore confidence in the regulation of building in Victoria. Sharon Knight, MP for Wendouree (Lab), 07.03.17

In 2017, after the Corkman Hotel demolition and Lacrosse fire, the teeth in s 16 were sharpened some more. If a “person in the business of building” knows that a building permit hasn’t been obtained when one should have been, for some or all of the work, they now face up to five years in gaol. No conditions are built in to protect the relatively innocent. As the MBAV said in a submission to parliament, this clause could apply to an illegal backyard gazebo. Beware staged permits or variations that may nudge the building works outside that allowed by the building permit. More at Lovegrove & Cotton.

A few more Corkmans and they’ll bring back hanging.

It’s now imperative for a Victorian building practitioners to know everything about a project’s building permit, before during and after their involvement. Still, how hard can that be?

Building permit registers

Under the then current s 16, the VBA was only able to charge the sub-sub-sub contractor who built the Swanston Street hoarding. His involvement was at the tail end of a five month old project. The magistrate noted that checking for a building permit is an easy thing to do, by looking at the council registry or inspecting the building permit set on site.

I questioned how easy this really was in last year’s article, suggesting that a search facility might help. Since then, the CoM introduced an online building permit register, and it is now the only way to find recent permits. This should be a step in the right direction, but unfortunately it requires a degree in database analysis to make good use of it. The database promises reliable and timely updates monthly, but the updates have been running about four months behind on the several times I’ve inspected it this year. It’s lack of usability and currency is perhaps reflected in its lack of popularity – barely 4,000 views since it was introduced. The dataset needs to be searchable and made easier for humans trying to assemble quotes at 1:30 in the morning.

Most Victorian councils offer no such register. This leaves it to council building departments to field what should be thousands of extra phone calls, if building practitioners actually understood their new obligations.

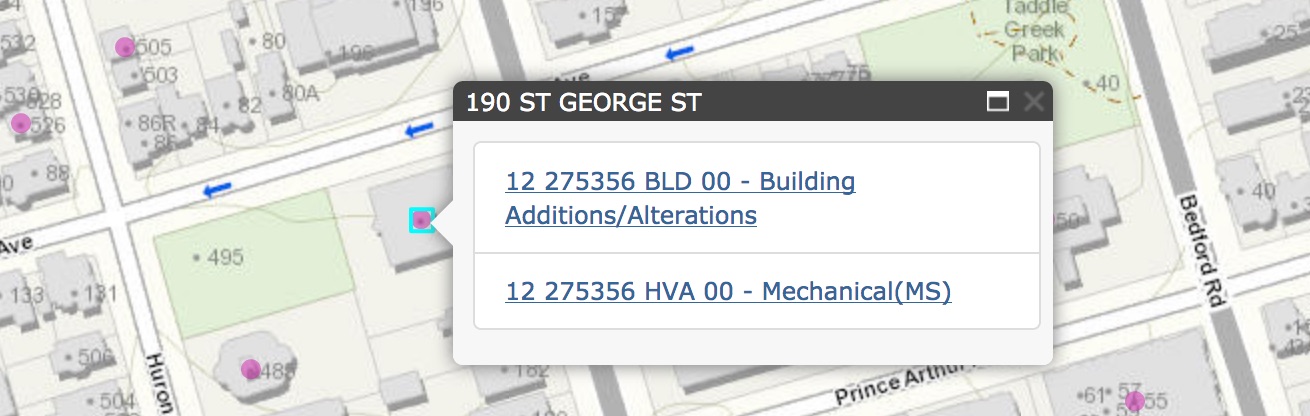

The Victorian Building Authority website holds building permit activity data from all issued permits across the state as it collects permit levies. Though its information is two months old and doesn’t include street addresses, perhaps this is the best starting point for the development of a simple state-wide solution. Something like the map-based tool used in Toronto.

If, after investigating, building practitioners cannot find trace of a building permit, then they need to find out promptly and definitively whether one ought to have been obtained – relying on a “she’ll be right” assurance from higher up the chain is no longer good enough. Unless the answer is plainly obvious, the path ahead can be a bit of a maze. Is there a building surveyor? Is there a planning permit? Is the work exempted from building permit requirements under the Building Act or Building Regulations or Planning Permit conditions or other stray by-law?

“These exemptions are extensive and require very, very careful scrutiny, cross referencing and professional advice, as there is a plethora of considerations that are factored into the question of whether building work is exempt from the requirement to obtain a building permit.” Kim Lovegrove, 2018

The changes to Section 16 may lead to a few fists through screens, and some expensive legal battles over the meaning of words, before they’re found to be unworkable.

Next in this series: Responsible Authorities

Posted by Peter on 10.08.19 in authorities

tags: brick, demolition, developers, safety, swanston street wall, wind

comment

Commenting is closed for this article.